Last summer the basketball player Ricky Rubio, a basketball wizard, retired before the World Cup. A serious setback for the national team. Before that, he was deeply affected by the death of his mother in 2018, then he suffered two serious knee injuries. In his statement he announced his temporary retirement “to take care of his mental health”.

Previously, in 2021 and during the Tokyo Olympics, Simone Biles, considered the best gymnast in the world, retired “because of an anxiety attack” while denouncing the great pressure on the stars of the sport. And they are certainly not the only ones, but they will not be on the front pages of the press.

Were they really suffering from a mental health problem or were they going through a personal rough patch? We don’t know. What we do know is that in the affluent West, so-called mental health cases have skyrocketed. Statistics are being published claiming that “40% of Spaniards suffer from poor mental health”.

Has mental illness skyrocketed exponentially or is this more of a terminological misunderstanding? It seems that we are calling “depression” the usual unhappiness, a state through which all human beings must inevitably pass, because life is full of professional burdens, heartbreaks, conflicts with children and parents, economic setbacks, duels, unforeseen events, illnesses… Such is our weak condition. What is happening now is that unhappiness has become medicalised under the name of “mental health problem”.

In the old days, when things went wrong, they gritted their teeth and moved on. But in this age of victimhood and narcissism we prefer to blame our problems on an external cause. Of course there are mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia, bipolar or manic-depressive disorders, and they should be treated with the utmost diligence and clinical professionalism. But not every downturn in life should be labelled as a “mental health problem”. Those that are and require careful medical treatment should not be trivialised.

The Christian faith reads human nature rather better. The Bible and the Gospels do see our fragile reality for what it is. They point out that the world is a vale of tears, that we are fallible and sinful, that there is no complete bliss here and that only the redemption of Jesus Christ grants us the possibility of full happiness after death.

To some it may seem a puerile tale to be overcome. But to others it seems wrong and simplistic to settle for the chimera that an ideology will be able to regenerate and make us happy on earth. And if it doesn’t work out, then nothing: “mental health problem” and new age pharmacopoeia and psychological quackery are the order of the day.

Of course: people who suffer from real mental health problems deserve all our attention and respect, they can have a terrible time and should be treated by professionals. But the whole story of this so-called “mental health” epidemic needs to be told. Because there is the depressed person on leave who was so seriously ill that he took advantage of the situation to complete his doctoral thesis. I have also heard of cases of depressed people on sick leave who, in the midst of certified suffering, uploaded to their Instagram “happy” photos of themselves sightseeing around the world with a smile from ear to ear.

Juan Carlos cmf

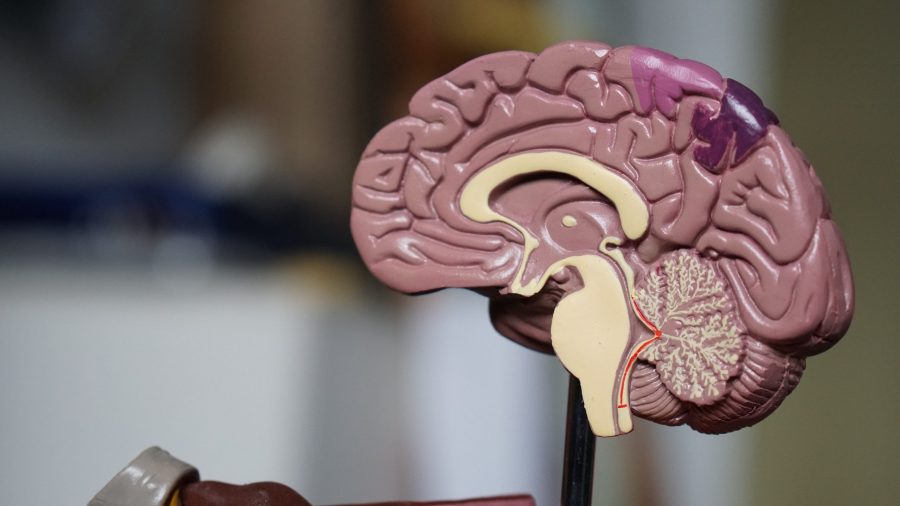

(PHOTO: Robina Weermeijer)