In my Congregation we have a tradition that we cannot make progress in our spiritual life if we do not dedicate an hour daily to personal prayer. And we uphold it, regardless of whether or not someone does not pray every day for whatever reason.

But does this rule apply to everyone? In principle, I am absolutely convinced of it. Moreover, I believe that it is an essential minimum for a Christian to keep his or her faith alive. Something like the doctors’ recommendation to walk at least one hour a day and drink about two litres of water to maintain good health.

But what about a mother with small children at home? The children demand her undivided attention. She can hardly have an hour to pray. It is impossible to pray surrounded by screaming or running children. Should she be convinced that, in her case, this is when she needs to pray the most? At this stage of my missionary life I would say something else: “If you are alone with your small children whose needs leave you very little time without interruptions, then you don’t need an hour of prayer every day. Raise your children with love and generosity, and that will produce the same effects as personal prayer”.

Without further clarification, this is a very dangerous statement. It would fall into the trap of the famous “heresy of action” which argued that action, any action, is already prayer. We would behave like that priest in a great cathedral who preached with a microphone disconnected from the current: he spoke, he moved, but nobody understood him. Our action must be linked to the Lord. He uses us as instruments. Our action is valuable as long as it is under cover and connected to God through prayer.

But when I argue that certain services can in fact be prayer, I find support in the authors of spirituality themselves. Carlo Carretto, one of the greats of the 20th century, spent many years in the Sahara desert in solitude. And he even confessed that his mother, who spent nearly thirty years raising children, was more contemplative than he was and much less selfish. But beware of the conclusions we draw from this! Carretto’s long hours of solitude in the desert were not mediocre, but there was something excellent about the years his mother lived among the noise and bustle of the little ones.

There are vocations that provide the perfect setting for a contemplative life. For them, ordinary life becomes a “domestic monastery”. A doctor, truly devoted to his patients, distances himself from the ways of the world and assumes a monastic rhythm of life. His tasks and preoccupations focus his time on his patients. Permanent contact with them gives him an extraordinary opportunity to learn empathy and altruism. His time is not his own, his personal needs must come second, and every time he turns around, a hand or a phone call calls out to him with real or apparent urgency. Years like that make anyone mature. That’s what St. Vincent de Paul calls it: “Leaving God for God“.

Juan Carlos cmf

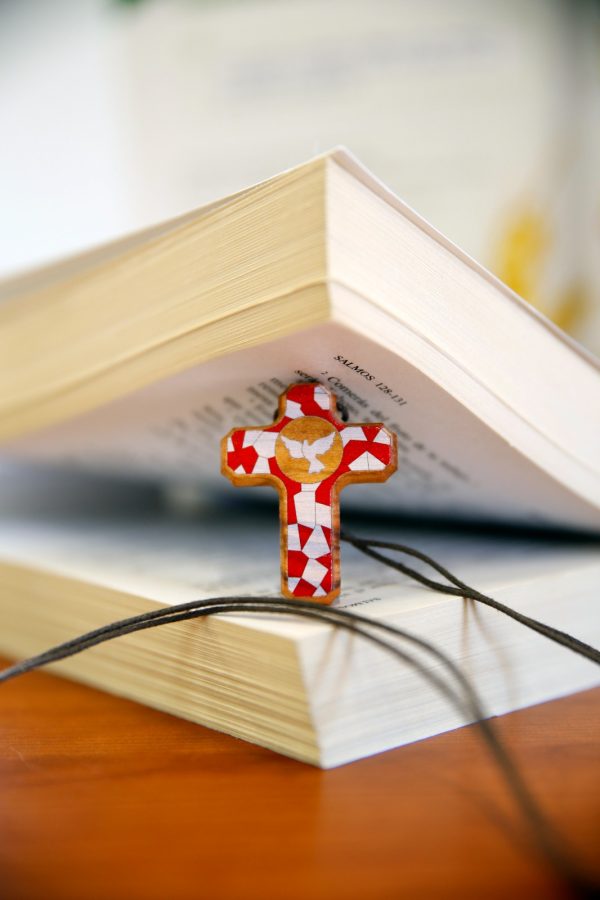

(FOTO: quasten)